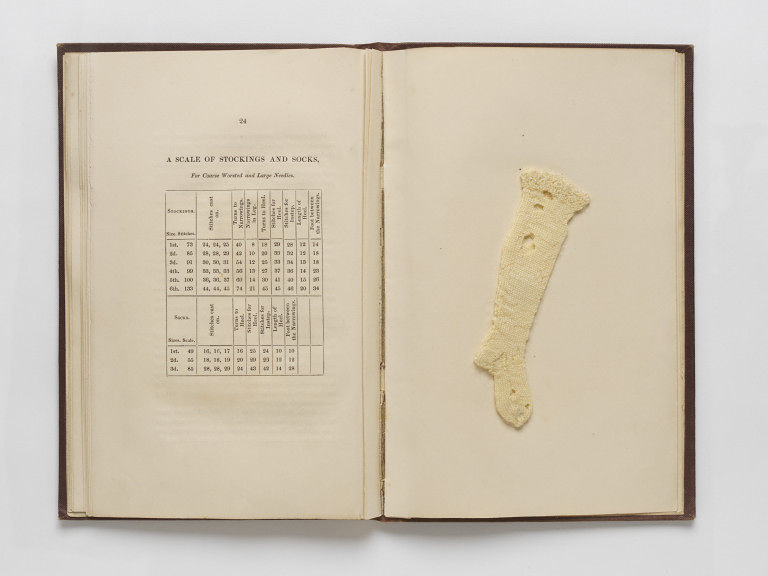

The economics of the time taken for hand-knitting and spinning during the 15th and 16th centuries was one of the motivating factors for inventing the knitting machine. The small size of knitting wires for fine knitting, and the variable yarn gauge of hand-made yarn, results in knitting to a specific garment size taking a long and variable amount of time. To quantify the likely time taken requires data on the speed of hand knitting. There hasn’t been much research or statistical analysis on the average knitting speed of an adult. At a 2018 event for Shetland knitters, the majority of experienced knitters were able to produce over 200 stitches in 3 minutes, which is just over 1 stitch per second.[1] A jumper back consisting of 150 stitches wide by 400 rows long requires 60,000 stitches. At 1 stitch per second the back would take 16.6 hours of knitting. The ‘scale of stockings and socks’ chart at the back of the Knitting teacher’s assistant provides cast on stitch count and rows for several sizes of sock and stocking, which can be used to calculate a rough stitch count of 7,000 – 16,000 stitches for a stocking, and between 1,700 – 6,000 for a sock. At 1 stitch per second a stocking takes between 2-5 hours, and a sock 1-2 hours, however the 1 stitch per second does not allow for time taken to increase and decrease stitches, and the time taken to move between double-pointed needles. These figures are very rough estimates that give an indication of the amount of time that knitting requires. As O’Connell Edwards notes knitting ‘was never a well-paid occupation’ and the sparse records that exist indicate 18d was paid for a dozen socks in the 1720s, and 2s 6d per week income for a full-time knitter in the Yorkshire Dales in the 1840s.[2] 2s and 6d is so low as to not indicate any purchasing power according to the National Archives’ historical currency converter.[3] Knitting is an excellent method to create warm and comfortable garments for the knitter and their immediate family, but scales poorly as a viable economic activity due to the amount of time it takes to complete a hand knitted garment.

During the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries increasing industrialisation of the textile industry and printing industry reduces the production time and cost of textiles, clothing and book manufacturing, moving knitting from the home to the factory. Industrialisation reduced the labour cost and production time for manufacturing knitted textiles resulting in increased profit and social unrest. The economic and political importance of the wool trade is evident in the woolsack that the Lord Speaker has sat on in the House of Lords since the fourteenth century.[4] Each stage of the textile industry transitioned from a hand-skill to a specialised machine. First scouring and carding, then spinning, and then the invention of the knitting frame by the Reverend William Lee in 1589.[5] Each advance in mechanisation resulted in thousands of home-working jobs being replaced with hundreds of factory workers. The mass unemployment resulted in riots so wide-spread and brutal that Parliament passed the Frame Work Bill.

Quote from Lord Byron in the Frame Work Bill: “During the short time I recently passed in Nottinghamshire, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on the day I left the county I was informed that forty frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection.” [6]

A competent knitter can adapt to knitting in a variety of

physical environments, and tools were developed to support knitting whilst

multi-tasking. There is a need to see the needles and stitches as a novice or

if working a complex pattern. There is less need to see the needles as knitting

experience increases. The blind were taught to knit both by hand and knitting

machine, and because they are taught to knit by touch, have less reliance on

good lighting.[7] Glass windows were expensive but knitting production is improved with good

light, especially machine knitting. Knitting machine factories place the

machines perpendicular to the windows to provide improved light, then squeeze

the knitting machines as close together as possible to fit as many in as they

can, which can be experienced at the Framework Knitters Museum in Ruddington.[8]

References

[1]

‘How

Do You Compare to the World’s Fastest Knitter?’, Interweave, 2018

<https://www.interweave.com/article/knitting/worlds-fastest-knitter/>.

[2]

O’Connell

Edwards, ‘Working Hand Knitters’, 74.

[4]

‘Woolsack’,

UK Parliament

<https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/building/cultural-collections/historic-furniture/the-collection/chairs-chairs-chairs/woolsack-/>.

[5]

Chris

Aspin, The Woollen Industry (Oxford, 2011), 22.

[6]

‘Frame

Work Bill (Hansard, 27 February 1812)’

<https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1812/feb/27/frame-work-bill>.

[7]

Frances

Lambert, The Hand-Book of Needlework (London, 1842), 186, British

Library.

[9]

Sandy

Black, Knitting : Fashion, Industry, Craft (London, 2012), 51–56, 104.

[10]

Marie

Hartley and Joan Ingilby, The Old Hand-Knitters of the Dales (Yorkshire,

1969), 77–80.

[11]

Black,

Knitting : Fashion, Industry, Craft, 104.

[12]

Anne

L. MacDonald, No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting,

Reprint edition (2010).